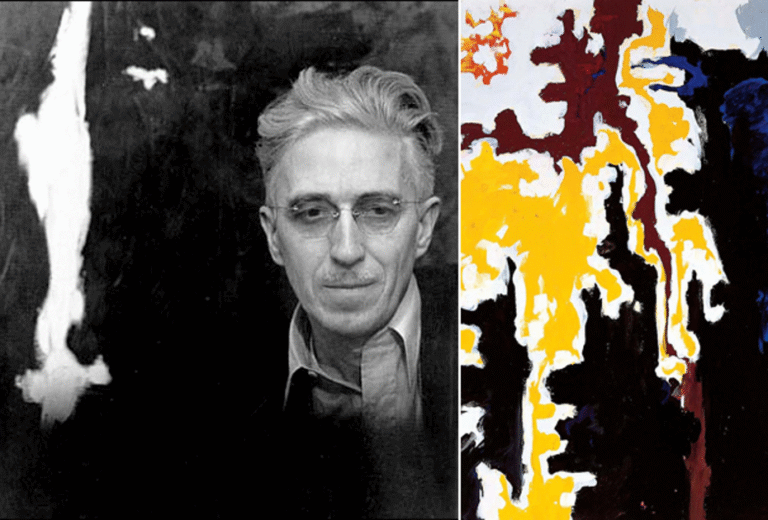

On view until September 14, 2025, the Clyfford Still Museum’s current exhibition, ‘Held Impermanence,’ guest-curated by Katherine Simóne Reynolds, draws deeply upon the collections and archives of the museum to explore a fascinating paradox: Still’s fierce desire for artistic control set against the inevitable aging and deterioration of his materials. The exhibition illuminates this tension between preservation and natural transformation, offering a fresh perspective on Still’s work and examining how art evolves over time.

Reynolds has brilliantly and boldly chosen to display pieces that bear visible marks of aging—paintings with condition issues that conservators might call “inherent vice.” These works reveal a vulnerability rarely associated with the famously uncompromising artist.

Some of Still’s works on paper hang behind protective curtains, which visitors may carefully lift for an intimate viewing experience. This thoughtful arrangement gives us a privileged peek, inviting us to consider not just Still’s artistic vision, but the physical reality of his creations as objects that breathe, age, and transform—much like their creator did throughout his remarkable career. While Still worked alongside celebrated Abstract Expressionists like Pollock, Rothko, and de Kooning, his reputation has followed a different trajectory. What qualities make Still’s powerful canvases uniquely his own, and why are audiences today increasingincreasingly drawn to the distinctive vision that set him apart from his more famous contemporaries?

Aesthetic and Philosophical Differences

Born in 1904 in North Dakota, Clyfford Still spent his formative years in the expansive landscapes of Washington state and Alberta, Canada. Unlike many of his contemporaries who gravitated towards European influences, Still’s aesthetics were distinctly American—with the vast wheat fields and rugged terrain of the Northwest shaping both his character and his artistic sensibility.

Still began his artistic journey with relatively traditional landscapes and figurative paintings. His early works, created during the Great Depression, often depicted farm laborers with angular, elongated bodies—foreshadowing the jagged forms that would later define his abstract style. While teaching at Washington State College in the 1930s, Still quietly began his transition toward abstraction, a path he would follow with singular determination.

“I never wanted color to be color,” Still once wrote. “I never wanted texture to be texture, or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse into a living spirit.”

The Isolationist of Abstract Expressionism

By the mid-1940s, Still had developed his signature style—monumental canvases with dramatic vertical forms suggesting fissures or flames, rendered in stark contrasts of color. What separated Still from his fellow Abstract Expressionists—Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning—wasn’t just his visual language but his fierce independence.

While the New York School gathered at the Cedar Tavern to debate art theory, Still largely kept to himself. He participated in important group exhibitions at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery and later at Betty Parsons Gallery, but even as his reputation grew, he remained suspicious of the art establishment. In 1950, he abandoned New York for rural Maryland, a self-imposed exile that would define the remainder of his career. This strategic withdrawal would significantly impact the availability of his works to come.

“I’m not interested in illustrating my time,” Still declared. “A man’s ‘time’ limits him, it does not truly liberate him.”