In recent decades, the global art scene has experienced a remarkable transformation, gradually shifting its focus eastward to embrace Korean artists’ understated yet profoundly expressive works. Monochrome painting, or Dansaekhwa, a genre born from Korea’s post-war turmoil, stands at the center of this shift. Now, this deeply Korean artistic movement is gaining widespread international recognition and appreciation, reflecting a broader global focus towards the East.

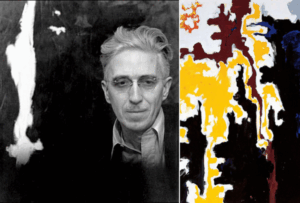

Born amid the sociopolitical upheaval of the 1970s, Dansaekhwa pioneers such as Chung Chang-Sup, Park Seo-Bo, Lee Ufan, Yun Hyong-Keun, Chung Sang-Hwa, and Ha Chong-Hyun sought transcendence through meditative artistic practices that emphasized process over end result. Their creations, distinguished by repetitive gestures and natural materials, speak to a universal yearning for serenity and introspection in chaotic times.

Dansaekhwa’s increasing prominence in the art scene signals a widespread reevaluation of art history, which recognizes the crucial role of non-Western artistic movements. As major exhibitions and prestigious auctions increasingly showcase these Korean masterpieces, it becomes evident that the global art community is not merely looking east but embracing a more inclusive narrative of creative innovation.

Origins of Dansaekhwa: Art Amidst Turmoil

The emergence of Dansaekhwa is inextricably linked to the profound trauma that defined 20th-century Korea. Following Japanese colonization (1910-1945) and the devastating Korean War (1950-1953), artists found themselves navigating a fractured society caught between military dictatorship, rapid industrialization, and an urgent search for national identity.

In this crucible of change, Dansaekhwa artists developed a visual language that responded to their circumstances while deliberately avoiding overt political statements that might trigger government censorship. Instead, they turned inward, creating works characterized by monochromatic palettes, textural explorations, and meditative repetition.

What distinguishes Dansaekhwa from contemporary Western movements is its spiritual foundation. While sharing visual similarities with Minimalism, Dansaekhwa was never about reduction for its own sake, but rather about connecting to deeper philosophical traditions rooted in Eastern thought. This quiet rebellion manifested in works emphasizing materiality and process—Park Seo-Bo’s rhythmic, pencil-traced canvases; Ha Chong-Hyun’s “back pressure” technique of pushing paint through hemp canvas; and Chung Chang-Sup’s incorporation of traditional Korean hanji paper made from mulberry bark.

Joan Kee, author of ‘Contemporary Korean Art: Tansaekhwa and the Urgency of Method’—the first comprehensive English-language study of this movement—notes that artists such as Lee Ufan, Park Seo-Bo, Yun Hyong-Keun, and Ha Chong-Hyun approached overwhelming forces like decolonization and authoritarianism through highly individual expressions. Their work challenged viewers to reconsider how they understood their world rather than why, emphasizing process and material engagement over explicit political messaging.

Note 1: Tansaekhwa and Dansaekhwa are identical terms referring to the same Korean monochromatic art movement, differing only in the romanization style of the Korean word ‘단색화.’

Note 2: In Korea, the family name comes first and is followed by the given name.